Why LLMs Aren’t AGI: Limits, Myths, and What’s Next

Large language models feel intelligent, but they lack goals, grounding, and reliable reasoning. Explore key limits, myths, and realistic paths forward.

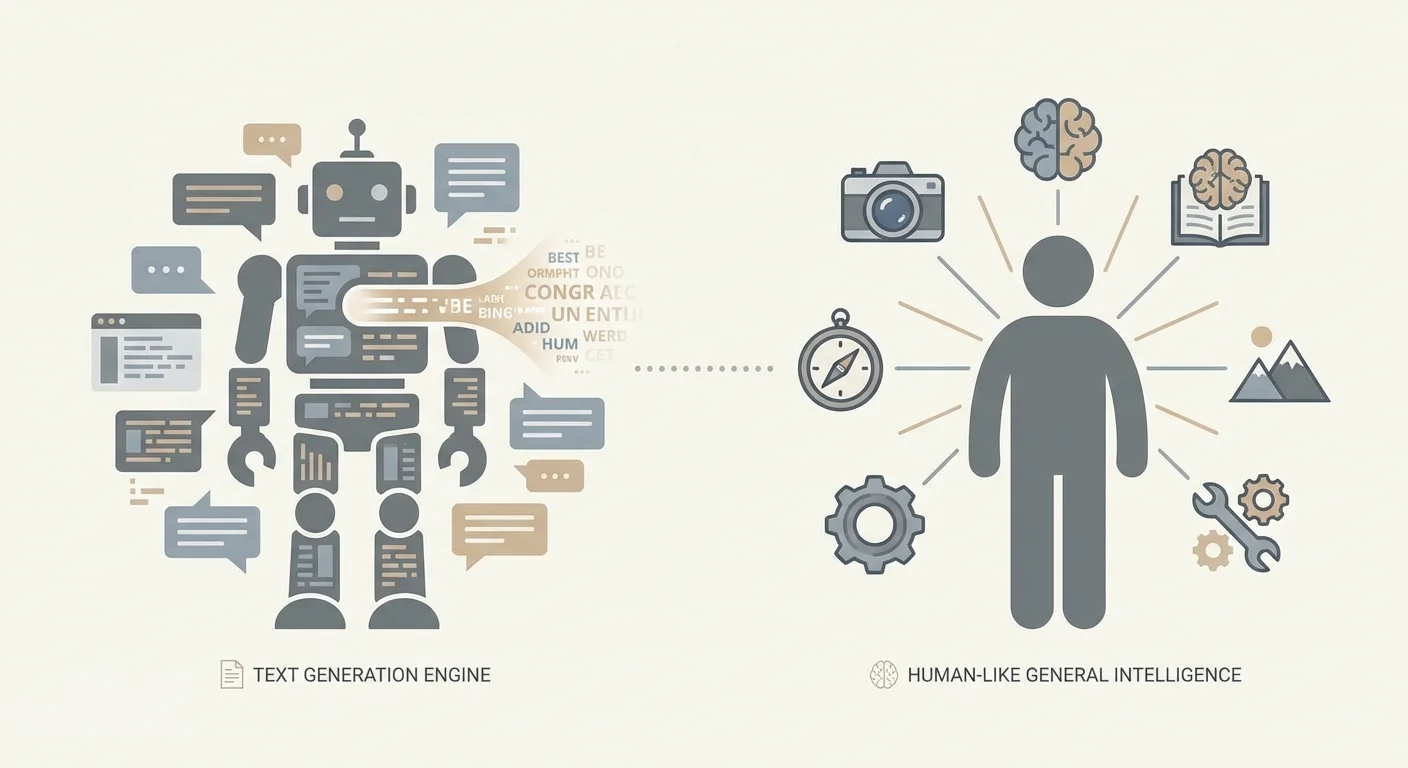

LLM vs. AGI: What We Mean by the Terms

Much of the “LLMs are (or aren’t) AGI” argument is really a terminology problem. People use the same words to mean different things, then talk past each other. Before debating what today’s systems can do, it helps to pin down the terms.

An LLM (Large Language Model) is a model trained to predict and generate text (and sometimes other modalities) from patterns in large datasets. It can be remarkably capable at explaining, summarizing, translating, coding, and chatting—because those tasks align well with language prediction. That capability alone doesn’t imply a stable understanding of the world, durable goals, or the ability to operate independently.

Narrow AI describes systems that perform well in specific domains or task families—spam filters, medical image classifiers, route optimization, and (arguably) most current LLM deployments. Narrow systems can be extremely powerful and economically important without being “general.”

AGI (Artificial General Intelligence) is a fuzzier term, but the practical idea is an agent that can learn and perform across a wide range of tasks and environments at human level (or beyond), with reliable reasoning, the ability to acquire new skills, and the competence to act over time without constant human scaffolding.

Even “generalization” can mean different things. Sometimes it means doing well on new phrasing of familiar tasks; sometimes it means transferring skills across domains; sometimes it means adapting to genuinely novel situations with minimal guidance. These are not equivalent. LLMs can excel at the first and still struggle with the latter.

This debate matters because real decisions get made based on it. Businesses may over-automate critical workflows, regulators may mis-target policies, and teams may underinvest in safety controls. In high-stakes settings—like software development and healthcare workflows (including EMR/EHR contexts)—an LLM’s confident output can look like competence until it fails on an edge case where correctness and traceability are non-negotiable.

This article doesn’t argue that LLMs are useless or “just autocomplete.” It argues that fluency is not the same as general intelligence, and that today’s LLMs have structural limits that keep them short of AGI.

Finally, “never” is a strong claim. Treat it here not as prophecy, but as a prompt: what would have to change—architecturally and at the system level—for an LLM-based approach to count as AGI in any meaningful sense?

How LLMs Work (Without the Hype)

Large Language Models are, at their core, extremely capable text predictors. They’re trained on vast collections of text and learn statistical regularities: which sequences of words tend to follow others, how ideas are commonly expressed, and which styles match which contexts. When you prompt an LLM, it doesn’t “look up” a stored answer or consult a world model in the way many people imagine. It generates the next token (a chunk of text) most plausible given the tokens so far, then repeats that step.

Training: learning patterns, not facts with guarantees

During training, the model sees a sequence of tokens and is asked to predict the next one. Over many examples, it adjusts internal parameters so its predictions improve. This creates an impressive ability to continue text in ways that sound coherent—because coherence is strongly correlated with the patterns found in the training data.

Scaling up data and compute often improves fluency and versatility for a simple reason: the model can represent more patterns and fit them more precisely. With enough capacity, it handles rarer constructions, follows longer contexts, and imitates specialized writing styles. None of that guarantees a stable, grounded understanding of what it’s saying; it indicates the model has become very good at pattern completion.

“Emergent” abilities: surprising, but not magic

Some capabilities seem to appear “suddenly” at larger model sizes—multi-step explanations, basic coding help, or more consistent instruction-following. Often, what’s happening is less mysterious: the model is combining familiar patterns in new ways, transferring a skill seen across many adjacent forms, or becoming reliable enough that users notice.

These jumps can feel dramatic, but they remain consistent with next-token prediction as the underlying objective.

Why conversation misleads us

Chatty interfaces encourage a human interpretation: confidence sounds like knowledge; a helpful tone sounds like intent; a well-structured explanation sounds like reasoning. But conversational skill is not the same thing as comprehension, goals, or truth-tracking. In practical deployments, the safest stance is to treat LLM output as a strong draft—not an authority.

Text Is Not the World: The Grounding Gap

A language model can produce convincing descriptions of reality without ever being in reality. Text is a record of human experience—summaries, stories, instructions, arguments—not the experience itself. When an LLM predicts the next word, it can sound like it “understands,” but it may simply be assembling patterns that correlate with understanding rather than the causal, perceptual grasp humans use to navigate the world.

What “grounding” means

Grounding is the connection between symbols (words, numbers, labels) and something outside the symbols: perception, action, and feedback. Humans learn what “hot” means by touching a warm mug, flinching, and remembering. We refine “heavy” by lifting, failing, adjusting grip, and trying again. That loop—sense, act, observe consequences—anchors concepts to reality.

A pure text model lacks that loop. It can recite that “glass breaks when dropped,” but it doesn’t own the expectation in a way that updates when conditions change (thick glass, rubber floor, low height). It usually has no direct channel to verify what’s true right now, in this situation, under these constraints.

Where “knowing words about things” breaks

Language-only patterns become a poor substitute for grounded interaction in several common situations. Physical causality often requires weighing multiple interacting factors rather than matching a single keyword. Spatial reasoning can fail when instructions depend on rotations, consistent 3D relationships, or mapping words onto a specific environment. Real-time contexts—inventory states, sensor readings, patient status—are especially risky because yesterday’s “typical” answer can be actively dangerous. And genuinely novel situations expose the core limitation: guessing what sounds right is not the same as being right.

Why this gap is central to AGI

AGI implies flexible competence across environments, not just eloquent commentary about them. Without grounding, an LLM can be a powerful assistant, but it remains vulnerable to confident error when the world demands verification, experimentation, or calibrated uncertainty.

This is also why many practical systems pair LLMs with tools: databases, sensors, simulators, and human checks. In applied work—especially healthcare workflows or safety-sensitive enterprise systems—grounding isn’t philosophical; it’s the difference between a helpful draft and an output you can safely rely on.

Reliability: Hallucinations, Fragility, and Truth

LLMs can sound certain even when they’re wrong. These failures are often called hallucinations: outputs that are fluent, detailed, and confidently stated—but not grounded in verified facts. The harder part is that tone is frequently indistinguishable from a correct answer, so casual “eyeballing” is a weak reliability strategy.

Why fluent text can drift away from truth

An LLM is trained to predict the most likely next token given its context. That objective rewards plausibility—what typically follows in similar text—more than truth-seeking. If the model lacks the needed information, it may still produce a best guess that matches the pattern of an answer. And even when the right information exists somewhere in training data, the model isn’t retrieving it like a database; it’s sampling from a learned probability distribution. As a result, correctness and the model’s core training objective can conflict.

Fragility under small changes

Reliability also breaks in quieter ways. Minor prompt edits—wording, order, extra constraints—can produce meaningfully different conclusions. Hidden constraints, such as long chat history or ambiguous requirements, can steer the output without the user noticing. This brittleness is a sign you’re not interacting with a stable “reasoning engine,” but with a sensitive generator whose behavior depends heavily on context.

Decision support vs. decision making

Because of hallucinations and prompt fragility, LLMs are best treated as decision support: drafting, summarizing, brainstorming, translating domain language, and proposing options. The moment you let them make decisions—approve a medical workflow change, sign off a compliance statement, or finalize financial logic—you inherit an error mode that can be both subtle and persuasive.

In production settings, teams reduce this risk by grounding responses in trusted sources or structured data, requiring evidence snippets within the workflow (not just confident claims), wrapping critical steps in deterministic validations (schemas, rules, unit tests), and keeping Human-in-the-Loop review for high-impact actions.

Reliability isn’t about making models “sound smarter.” It’s about designing systems where sounding right is never enough.

Reasoning Isn’t Guaranteed by Fluency

A persistent misconception is that if a model can sound like it’s reasoning, it must be reasoning. LLMs generate the next token that best fits training patterns and the immediate context. That process can imitate step-by-step logic—sometimes impressively—without reliably enforcing the constraints real reasoning requires: consistency, completeness, and error checking.

Where LLM “reasoning” feels real

LLMs often do well when good answers are strongly correlated with familiar linguistic patterns: drafting explanations, summarizing tradeoffs, proposing plausible solutions, or producing code that resembles common implementations. Even when the model isn’t proving anything, it can still be an effective heuristic engine: it suggests approaches a human can validate.

Where fluency breaks down

The trouble appears when the task demands strict, long-horizon correctness rather than plausible narration. Multi-step logic can collapse when an early mistake contaminates everything downstream. Proof-like problems require airtight constraints, not persuasive prose. Edge cases and rare conditions may be underrepresented in training text. Conflicts between instructions, assumptions, and hidden dependencies can pull the completion in inconsistent directions. And “answer-shaped” responses can skip verification precisely because they read well.

Why tools and verification layers matter

The picture changes when the LLM is a component inside a system that can check itself. External tools (calculators, interpreters, formal solvers), retrieval of authoritative data, and structured verification (unit tests, consistency checks, cross-model critique, Human-in-the-Loop review) can turn fluent suggestions into trustworthy outcomes.

That doesn’t make the base model an AGI. It makes it a powerful interface for generating candidates—while the rest of the system does the work of grounding and correctness.

Agency and Goals: The Missing Ingredients

When people imagine AGI, they usually picture something with agency: it can form goals, stick with them over time, plan actions to reach them, observe what happened, and adjust based on feedback. Agency isn’t just “doing tasks.” It’s persistent, self-directed behavior across changing situations.

Most LLMs, by default, don’t have that. A chat model generates the next token given the prompt. It can talk about goals, plans, and intentions with impressive fluency, but it doesn’t intrinsically want anything, and it doesn’t keep pursuing objectives when the conversation ends. Without an external loop, it has no stable target, no ongoing feedback from the world, and no mechanism to decide what to do next beyond responding.

Chat completion vs. agentic systems

A chat completion setup is reactive: you ask, it answers. An agentic architecture wraps the model in scaffolding that provides persistence and control—task queues, tools (APIs), memory stores, planners, and evaluators that check outcomes. In that setup, the system exhibits agency-like behavior; the language model is one component.

This distinction matters in practice. If an “AI assistant” can schedule jobs, modify records, or trigger deployments, the riskiest part isn’t the model’s writing ability—it’s the permissions and decision loop wrapped around it.

Why added agency raises stakes

Giving a model tool access and autonomy can amplify ordinary failure modes. It may pursue the wrong objective, over-interpret vague instructions, or act on incorrect assumptions. The fix isn’t “a smarter model” alone; it’s safeguards: clear goal specifications, constrained tool access, approvals for high-impact actions, monitoring, and tight evaluation against real outcomes.

Memory, Identity, and Continuity Over Time

LLMs can sound consistent within a single conversation, but that “continuity” is often an illusion created by a short-term context window. Within that window, the model can reference what you just said and maintain a coherent tone. Outside it—across longer sessions, days, or real-world tasks—there is no inherent durable self, stable beliefs, or persistent understanding of your goals.

Short context isn’t long-term memory

What people call “memory” in an LLM is usually just text that’s still visible in the prompt. It’s closer to working memory than a life record. Once earlier details fall out of the context window, the model doesn’t remember them; it guesses what would be plausible.

General intelligence, as people usually imagine it, depends on continuity: learning from mistakes, accumulating reliable facts, revising beliefs, and staying aligned with long-term objectives even when the conversation resets.

Identity and preference drift

Without persistent state, LLMs can contradict themselves across sessions: a tool that “prefers” one approach today may recommend the opposite tomorrow, not because it updated its worldview, but because it’s sampling a different completion. Even within the same session, small prompt changes can produce shifting priorities or a new interpretation of what the user meant.

That fragility matters for real tasks—requirements gathering, medical documentation workflows, multi-week software projects—where consistency and traceability are as important as eloquence.

Adding memory with retrieval and structured state (and what it doesn’t solve)

To compensate, teams bolt on external memory: retrieval systems, databases, user profiles, and structured state that gets re-injected into the prompt. This can dramatically improve continuity, and it’s common in production systems.

Typical layers include conversation summaries, retrieval from documents or knowledge bases, user preference profiles and permissions stored in a database, and structured task state (decisions made, open questions, constraints). But these are scaffolds around the model, not an internal, self-maintaining identity. Retrieval can surface the wrong fact, summaries can erase nuance, and the model can still misinterpret stored state.

In practice, reliable long-term behavior usually requires careful system design plus Human-in-the-Loop checks.

Generalization Beyond the Training Distribution

AGI—if it ever exists—has to do more than perform well on familiar patterns. It should transfer what it knows to genuinely new domains, rules, and goals, especially when the “right answer” can’t be found by remixing what looks like past examples.

Generalization vs. “looking similar enough”

A lot of LLM success is better described as powerful interpolation: producing outputs consistent with the statistical structure of the data they absorbed. When a task resembles common training-time formats—explanations, summaries, code patterns, customer support scripts—LLMs can appear broadly capable.

But interpolation is not the same as generalization in the AGI sense. A model can be excellent at completing patterns and still fail when a task demands learning a new rule on the fly, building a stable internal model of an unfamiliar environment, or updating beliefs when observations contradict the initial guess.

Out-of-distribution failures are not edge cases

Real work constantly creates out-of-distribution situations: new regulations, new product constraints, unexpected user behavior, tool interfaces that change, datasets with novel schemas. LLMs often degrade sharply when the surface form changes or when success depends on hidden constraints rather than textual plausibility.

Trouble tends to show up when new rules contradict common conventions, when actions matter more than wording (multi-step tool use under constraints), when rare concept combinations appear, or when instructions are adversarial or ambiguous—conditions where “sounding right” is easy and being right is hard.

Why benchmarks can flatter capability

Benchmarks are useful, but they’re often optimized for comparability, not surprise. Once a benchmark becomes popular, it shapes training, prompting strategies, and evaluation norms. Scores rise while the real question—“Will it handle the next thing we didn’t think to test?”—remains.

For businesses, this gap is operational: a system can look “AGI-ish” on internal demos yet fail when a customer workflow deviates from your test set. Production systems typically need constrained interfaces, verification steps, and human escalation for truly novel cases.

Alignment and Safety: Capability Isn’t Enough

When people argue that a highly capable model is “basically AGI,” they usually focus on what it can do in a demo. Alignment asks a different question: does the system reliably pursue the user’s intent within human constraints, even when the prompt is unclear, adversarial, or morally loaded?

In practice, alignment means matching goals (what the user wants), values (what society permits), and boundaries (privacy, legality, safety policies, operational rules) across messy situations.

Why RLHF helps—and why it doesn’t solve it

Instruction tuning and RLHF (training from human feedback) can make a model more cooperative and less toxic. But they don’t turn the model into a consistently principled reasoner. The system is still learning patterns of preferred responses, not understanding human values.

Alignment is also not one objective. You’re balancing ideals that can conflict: helpfulness, honesty, safety, privacy, and fairness. Optimizing one often pressures the others. A model trained to be maximally “helpful” may over-answer and speculate; a model tuned for strict safety may refuse benign requests; a model that is highly cautious may frustrate users and push them into unsafe workarounds.

Why AGI claims must include governance

If “AGI” means a system that can act broadly and competently, safety cannot be an afterthought—greater capability increases the blast radius of mistakes. Real deployments need governance: clear policies on allowed use, logging and auditability, access control, Human-in-the-Loop review for sensitive workflows, and incident response when the system behaves unexpectedly.

In high-stakes products, alignment is less about slogans and more about engineering discipline: guardrails, evaluations, monitoring, and accountability. Capability gets attention; safety earns trust.

Can LLM-Based Systems Become AGI? What Would Need to Change

The key question isn’t whether an LLM can be “upgraded” into AGI by bolting on tools. It’s whether adding perception, memory, and action closes the fundamental gaps: reliable reasoning, grounded understanding, and coherent long-horizon behavior.

Tools help—but they don’t magically create understanding

Hybrid systems already look far more capable than a chat-only model. An LLM that can search, retrieve documents, run code, call APIs, and check its own work will appear “smarter” on many tasks. In practice, this approach reduces errors: retrieval can anchor answers in authoritative sources, and execution can verify math and logic.

But tool use mostly changes performance, not the nature of the model’s core cognition. The LLM remains a probabilistic generator of text; the surrounding system must constrain it, validate it, and decide when to trust it.

What would move systems meaningfully closer to AGI

If we avoid labels and talk about architectures, several shifts matter more than simply making models bigger:

- Grounded world models: learning tied to perception and interaction, not just text.

- Verified reasoning pipelines: systematic checking (execution, formal methods, proofs, consistency tests) as a default, not an option.

- Persistent memory with governance: durable, editable knowledge and user-specific context without uncontrolled drift or privacy risk.

- Planning and control loops: explicit goal decomposition, monitoring, and recovery from failure over long time horizons.

- Training for truth and calibration: systems that can abstain appropriately and reliably signal uncertainty.

Why capability-first language is safer than “AGI”

“AGI” compresses many properties—reliability, autonomy, transfer, robustness, safety—into one word. Describing systems in terms of what they can do, under which constraints, and with what failure modes is more honest and more useful for engineering and risk management. It also avoids the common trap of mistaking impressive demos for general, dependable intelligence.

Practical Takeaways for Businesses Building with LLMs

LLMs can deliver real value today—if you treat them as probabilistic assistants, not autonomous “understanding” engines. Strong deployments start with clear scope: what decisions the model may influence, what it must never decide, and what evidence it must provide when it produces an answer.

Use LLMs in assistive roles with guardrails: protect inputs (privacy filters, prompt templates, constrained tool access) and constrain outputs (format checks, grounding in internal sources when possible, and explicit uncertainty where needed). For high-impact workflows—healthcare, finance, legal, safety-critical operations—require Human-in-the-Loop review and make the reviewer’s job easier by surfacing the relevant source context next to the model’s draft.

Auditing is a simple but often overlooked practice: sample outputs regularly, label failures (hallucination, omission, unsafe suggestion, policy violation), and feed those labels into prompt updates, retrieval tuning, routing rules, and evaluation tests.

A concise rule of thumb:

- Use LLMs for drafts, summaries, extraction, and Q&A over controlled internal knowledge.

- Don’t rely on them as the source of truth, or for irreversible approvals and open-ended automation without constraints.

If you’re turning these ideas into production software—especially in regulated domains—teams like SaaS Production (saasproduction.com) often focus on system design over hype: AI integration paired with Human-in-the-Loop review, structured checks, and traceability so speed gains don’t come at the cost of reliability.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is an LLM in practical terms?

An LLM (Large Language Model) is primarily a probabilistic text generator trained to predict the next token from patterns in large datasets. It can be extremely useful for language-shaped work (drafting, summarizing, translating, coding assistance), but that doesn’t automatically provide: - grounded understanding of the real world - reliable truth-tracking - durable goals or self-directed behavior over time

What do people usually mean by AGI?

AGI is typically meant as broadly capable intelligence that can learn and perform across many environments at (or above) human level with reliable reasoning and the ability to operate over time without constant human scaffolding. In practice, it implies robustness, skill acquisition, planning, and consistent performance on genuinely novel situations—not just fluent responses.

Why do debates about “LLMs vs. AGI” get so confused?

Because “generalization” is used to mean different things. A model can generalize to new wording of familiar tasks (often a strength of LLMs) while still failing to: - transfer skills to new domains with new rules - adapt based on real-world feedback - maintain correctness under edge cases and distribution shifts

What is the “grounding gap,” and why does it matter?

Grounding is the connection between symbols (words) and real-world perception/action/feedback. Humans learn concepts through interaction (sense → act → observe → update). A text-only model can describe the world convincingly without having a direct way to verify what’s true *right now* in a specific environment, which is a core gap for dependable autonomy.

Why do LLMs hallucinate even when they sound confident?

Hallucinations happen because the model is optimized for *plausible continuation*, not guaranteed truth. If needed information isn’t present in the prompt (or is ambiguous), the model may still produce an answer-shaped response that reads well. Operational mitigations often include: - requiring citations from approved internal sources (within the workflow) - retrieval from trusted data stores - deterministic validation (schemas, rules, unit tests) - Human-in-the-Loop review for high-impact outputs

Why are LLM outputs so sensitive to prompt wording?

LLM behavior can change significantly with small prompt edits, different ordering of constraints, or hidden context in a long chat. This is a sign you’re interacting with a context-sensitive generator rather than a stable “reasoning engine.” To reduce fragility: - use templates with consistent structure - keep requirements explicit and testable - add automated checks (format, constraints, invariants) - evaluate with a fixed test set before deploying changes

Do LLMs actually reason, or just mimic reasoning?

Not reliably. LLMs can imitate step-by-step reasoning and often propose good candidate solutions, but they may skip verification, drift mid-chain, or break on rare constraints. A safer pattern is: - let the LLM generate options - verify with tools (executed code, calculators, solvers) - enforce correctness with tests and reviews - treat the final decision as a controlled system outcome, not a free-form completion

What’s the difference between a chat model and an “agent”?

By default, most LLMs are reactive: they respond to prompts but don’t persist goals or act unless a surrounding system gives them memory, tools, and a control loop. Adding agency (APIs, write access, automated actions) increases the blast radius of ordinary failures. Practical safeguards include least-privilege tool permissions, approvals for irreversible actions, monitoring, and clear escalation paths.

Why don’t LLMs have real long-term memory or consistent identity?

What people call “memory” is often just the conversation text still inside the context window. Once it falls out, the model doesn’t remember—it guesses. To get continuity, teams typically add external state: - structured task state (decisions, constraints, open questions) - retrieval from vetted documents - user permissions and preferences stored outside the model Even then, you still need governance (what can be stored, who can access it, how it’s corrected) and checks for mis-retrieval or misinterpretation.

How should businesses use LLMs safely in production (especially in regulated domains)?

Focus on capabilities and failure modes, then design the system around them: - Use LLMs for drafts, summaries, extraction, and Q&A over controlled internal knowledge. - Don’t use them as the source of truth for medical, legal, financial, or compliance approvals. - In healthcare and EMR/EHR-adjacent workflows, require traceability, audit logs, and Human-in-the-Loop review. - Add deterministic safeguards (schemas, rules, unit/integration tests) and routine output auditing. The goal is speed *with* reliability: treat the model as a component inside a verified workflow, not as an autonomous authority.